|

Eswar Prasad, by his own telling, is a little more of a short term optimist and a little more of a long term pessimist on China due to his recent visit and observations.

0 Comments

Economics for Public Policy post from Miles Croak(Thanks Brent)

3. Policies to turn to: How to make work pay There is no one answer, and not all options involve governments tinkering with tax rates. But some do. One important step is to make work pay. There is a grain of truth to the traditional storyline: a new economy requires a new way of supporting incomes. It is not simply unemployment insurance that Canadians need, but wage insurance; it is not simply a guaranteed income that Canadians need, but a participation income. And we have precedents for delivering income support in these ways. The Working Income Tax Benefit is a good example. It can be thought of as a “social wage” that encourages a participation society by topping up wage rates, and offering a guaranteed income conditional on working. But in its current configuration is much too small to have significant bite for anything other than a small part of the population. Benefits from the program begin to kick in once someone makes more than $3,000, then amount to 25 cents for every extra dollar earned, then top out at just under $1,000 for singles and about $1,800 for families. Benefits fall by 15 cents for every dollar a family earns beyond about $15,650, disappearing altogether at earnings of about $28,700. Some parts of our Employment Insurance program also have a design of this sort, allowing Canadians to work while still collecting a fraction of their benefits. This is smart income transfer policy for a jobs market that is more and more polarized, and it is not hard to imagine that an expansion of the Working Income Tax Benefit that folds into a restructured Employment Insurance program could become a social wage, offering Canadians both the kind of income support and wage insurance they need to stay engaged with a more polarized jobs market. In other words with a more nuanced interpretation of the facts it is not hard to give credence to another storyline about income inequality that goes something like this. Inequality has increased; there is something that can be done about it; and if public policy has punch, the effort directed to fighting inequality contributes to solving other pressing problems, like poverty. The Upshot (NY TIMES)

Next week, when Federal Reserve officials meet to decide whether to raise interest rates for the first time in nine years, one question will be front and center: How much faith should be placed in a line on a graph first drawn by a New Zealand economist nearly six decades ago, based on data on wages and employment in Britain dating to the 1860s? That would be the Phillips curve, one of the most important concepts in macroeconomics. It shows how inflation changes when unemployment changes and vice versa. The intuition is simple: When joblessness is low, employers have to pay ever higher wages to attract workers, which feeds through into higher prices more broadly. And inflation is particularly prone to rise when the unemployment rate falls below the “natural rate” at which pretty much everybody who wants a job either has one or can find one quickly. As the Fed’s chairwoman, Janet L. Yellen, put it in a 2007 speech, the Phillips curve “is a core component of every realistic macroeconomic model.” Except it doesn’t work. Or at least, it hasn’t worked very well in the last few decades in the United States. And it has proved particularly problematic to try to use that historical relationship to predict where inflation is going. That is why a longstanding academic debate is now at the core of the Fed’s policy debate. Ms. Yellen and many of her Fed colleagues have indicated that they think they should raise interest rates this year, in part because the Phillips curve suggests there will be excessive inflation if they don’t. The unemployment rate was 5.1 percent in September, just a smidgen above the 4.9 percent that Fed leaders believe is the appropriate jobless rate in the longer run. In other words, if you believe in the traditional Phillips curve, inflation should be taking off any day now. But this month, two Fed governors, Lael Brainard and Daniel K. Tarullo, argued against a rate move. Ms. Brainard said that the Phillips curve relationship was “at best, very weak at the moment.” Mr. Tarullo said that it was “probably wise not to be counting so much on past correlations, things like the Phillips curve, which haven’t been working effectively for 10 years now.” It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that the Fed’s rate decision this year will be based on whether its leaders really believe that the Phillips curve is useful in describing how the economy works in 2015. Wage inflation is on the rise view: From Brad DeLong Must-Watch: Really, really bad news for the American economy. Alan Krueger concludes that we are now near "full employment" in a monetary policy-Federal Reserve-inflation sense. The implications? The implications are:

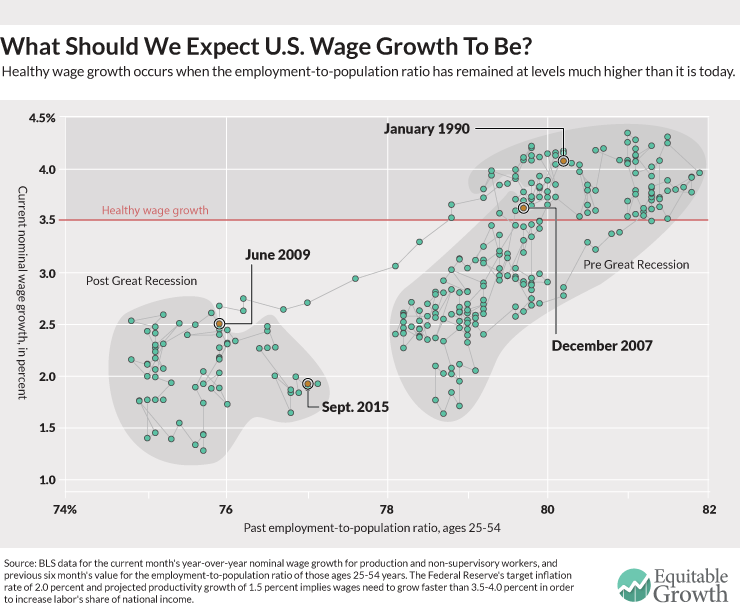

Alternative view (Ironically from WCSG and Matt Phillips) To understand the changes in the overall inflation Phillips curve, it might be useful to look at another version of the curve: the relationship between unemployment and “wage inflation,” better known as wage growth. Now, that curve doesn’t look that great either, but that might be because the unemployment rate is currently overstating the health of the labor market. If we take a look at the relationship between wage growth and another measure of labor market slack, however, the relationship might hold up. The graph shows the relationship between wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, and the employment rate for prime-age workers six months prior. It clearly shows that when the labor market is tighter (when the employment rate is higher), wage growth is stronger. Reuters

raq's oil exports have averaged 3.20 million barrels per day (bpd) so far in June, according to loading data and an industry source, setting shipments from OPEC's second-largest producer on course for a record high. Another boost from Iraq underlines the focus of major members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries in keeping market share, not restraining supply to support prices. OPEC met on June 5 and kept its policy unchanged. Exports from Iraq's southern terminals have averaged 3.00 million barrels per day (bpd) in the first 15 days of June, according to shipping data seen by Reuters and an industry source, up from 2.69 million bpd in all of May. Zerohedge. Brent called it.

And on that note, we'll close with the following from Citi's Willem Buiter: Fiscal policy can undoubtedly come to the rescue and prevent a recession in China. But what is needed is not another dose of the familiar post-2008 fiscal medicine: heavy-lifting capital expenditure on infrastructure with dubious financial and social returns, and capital expenditure by SOEs that are already struggling with excess capacity, all funded, as if these were commercially viable ventures, through the banking or shadow banking sectors. As regards funding the fiscal stimulus, only the central government has the deep pockets to do this on any significant scale. The first-best would be for the central government to issue bonds to fund this fiscal stimulus and for the PBOC to buy them and either hold them forever or cancel them, with the PBOC monetizing these Treasury bond purchases. Such a ‘helicopter money drop’ is fiscally, financially and macro-economically prudent in current circumstances, with inflation well below target and likely to fall further. Quartz

Vincent Tinto is a professor at Syracuse University. He’s well known for his theories on students’ persistence through higher education. His research produced what’s known as the “Model of Institutional Departure.” Tinto’s model informs us that, above all else, college is a transition from one community to another. Our success in college depends on how well we integrate ourselves into that new community. What happens if we go home every weekend to visit high-school friends and sweethearts instead of making friends in our new community? We don’t integrate. We don’t get help from new friends going through the same issues or receive academic advice from new mentors. Instead, we tend to drop out. Tinto’s model has proven incredibly useful in improving how we educate not just undergraduates but people enrolled in remote learning programs and continuing-education classes. And it can be extended far past education to help us understand how people persist. Notre Dame psychologist and computer scientist D’Mello, whose research areas include artificial intelligence, human-computer interaction and the learning sciences, together with Art Graesser of the University of Memphis, collaborated on the study, which was funded by the National Science Foundation.

They found that by strategically inducing confusion in a learning session on difficult conceptual topics, people actually learned more effectively and were able to apply their knowledge to new problems. Scientific American The subjects watched an animated tutor and student discuss possible flaws in a scientific study. The researchers had the animated tutor and student disagree with each other on specific flaws. But to set up a really confusing situation for one group of subjects they also had the pretend tutor and student make incorrect or contradictory statements about the study. Then the subjects had to decide which of the two opinions had more scientific merit. Subjects who were forced to deal with the incorrect and contradictory statements did significantly better on later tests where they had to spot flaws in studies, as opposed to those subjects who only faced the disagreements between the animated tutor and student. The study will be published in the journal Learning and Instruction. Researchers note that confusion motivates us to work harder to understand, and so we gain a deeper and more comprehensive knowledge of a subject. Quartz

Students who are presented with unfamiliar concepts, asked to work through them, and then taught the solution significantly outperform those who are taught through formal instruction and problem-solving. The approach is both utterly intuitive—we learn from mistakes—and completely counter-intuitive: letting kids flail around with unfamiliar math concepts seems both inefficient and potentially damaging to their confidence. Kapur believes that struggle activates parts of the brain that trigger deeper learning. Students have to figure out three critical things: what they know, the limits of what they know, and exactly what they do not know. Floundering first elevates the learning from knowing a formula to understanding it, and applying it in unfamiliar contexts. Calculated Risk

A personal comment ... Over the last several years, I noted on several occasions that Congress has been a disaster. They've opposed economic policies normally supported by both parties - and by Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan - and this has hurt the economy. Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke noted in his book: “I also felt frustrated that fiscal policy makers, far from helping the economy, appeared to be actively working to hinder it.” emphasis added I agree with Bernanke. This seems to part of a defeatists theme of the current Congress - an overwhelming pessimism about several policies -"Nothing can be done" could be their slogan (or worse when they "actively work to hinder" the economy). Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke also wrote in this book that he “lost patience with Republicans’ susceptibility to the know-nothing-ism of the far right." He went on to write: “I often said that monetary policy was not a panacea — we needed Congress to do its part. After the crisis calmed, that help was not forthcoming.” emphasis added And here is another excerpt from Bernanke's book via the WSJ, Bernanke on Congress: "They blamed the crisis on the Fed and on Fannie (Mae) and Freddie (Mac), with little regard for the manifest failings of the private sector, other regulators, or, most especially, Congress itself. They condemned bailouts as giveaways of taxpayer money without considering the broader economic consequences of the collapse of systemically important firms. They saw inflation where it did not exist and, when the official data did not bear out their predictions, invoked conspiracy theories. They denied that monetary or fiscal policy could support job growth, while still working to direct federal spending to their own districts. They advocated discredited monetary systems, like the gold standards. This defeatist view - and pessimistic outlook - applies to other policies too. As an example, during the recent debate, GOP presidential hopefuls Marco Rubio and Carly Fiorina acknowledged the dangers of climate change (a positive step compared to the deniers), but both said Nothing Can be Done. How sadly pessimistic and contrary to the optimism of Presidents Kennedy and Reagan. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed