|

0 Comments

Via FT

The International Monetary Fund has called on the Bank of Japan to expand its monetary easing in an all-out effort to push inflation to 2 per cent. In a dramatic intervention, the IMF warned Tokyo that the risks to Japan’s economy “are tilted to the downside”, and called for reinforcement to all three arrows of the Abenomics stimulus. The IMF‘s call will pile pressure on Haruhiko Kuroda, BoJ governor, to take more action just as he signalled a move the other way — keeping monetary policy on hold, and striking a more upbeat tone on Japan’s economy. The clash highlights growing tension more than two years after the start of prime minister Shinzo Abe’s three-pronged stimulus, with signs of stronger growth, but inflation still hovering close to zero. Mr Kuroda insists the BoJ’s massive stimulus is working as planned, with rising incomes driving a “virtuous cycle” towards higher inflation, but the IMF said “the desired regime shift has not yet materialised” HBR

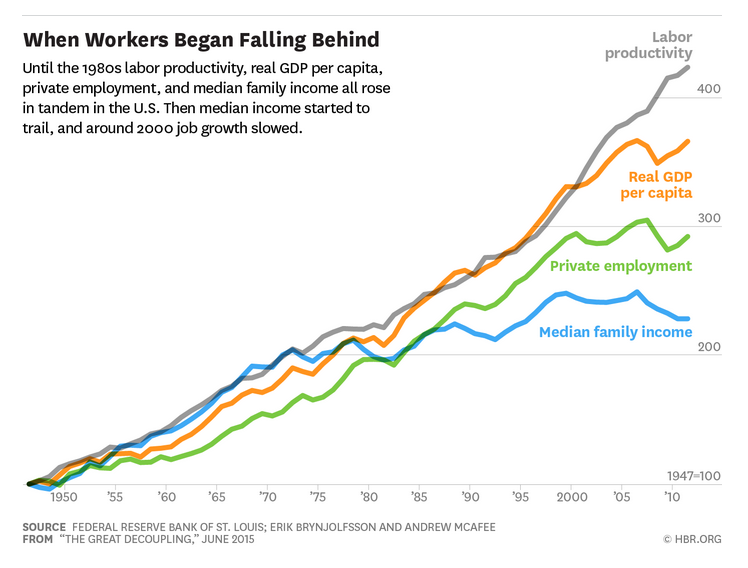

Brynjolfsson: Let’s look at the four key measures of an economy’s health: per capita GDP, labor productivity, the number of jobs, and median household income. When we studied the U.S. data on all those metrics, we turned up an intriguing story: For more than three decades after World War II, all four went up steadily and in almost perfect lockstep. Job growth and wage growth, in other words, kept pace with gains in output and productivity. American workers not only created more wealth but also captured a proportional share of the gains. In the 1980s, however, the growth in median income began to sputter. In the past 15 years it’s turned negative; once you adjust for inflation, an American household at the 50th percentile of income distribution earns less today than it did in 1998, even after accounting for changes in household size. Job growth in the private sector has also slowed—and not just because of the 2008 recession. Job gains were anemic throughout the 2000s, even when the economy was expanding. This phenomenon is what we call the Great Decoupling. The two halves of the cycle of prosperity are no longer married: Economic abundance, as exemplified by GDP and productivity, has remained on an upward trajectory, but the income and job prospects for typical workers have faltered. Washington Center for Equitable Growth

May Day celebrations kicked off around the world late last week, with unionists in many countries decrying the rise of income inequality in their countries. The United States, of course, celebrates Labor Day in September. But in the spirit of adding an American voice to the larger international commentary, here’s a post-May Day analysis of what economists think about income inequality in this country. Income inequality has increased in the United States over the past 30 years, as income has flowed unequally to those at the very top of the income spectrum. Current economic literature largely points to three explanatory causes of falling wages and rising income inequality: technology, trade, and institutions. The existence of different explanations points to the difficulty of pinning down causes of inequality. Part of this difficulty is rooted in the complexity inherent in larger labor market inequalities. Falling labor force participation, stagnating median wages, and declining share of labor income, for example, are all part of current U.S. labor market trends. These trends are certainly connected, but they also have been studied through various research frameworks, which can inexorably lead to different policy implications. Acknowledging the complex and intertwined nature of these explanations is crucial to developing policy solutions that address the joint causes of inequality. Of the three explanations for rising inequality, the so-called technology-and -education argument is the most prominent. This hypothesis focuses on the large wage premiums for workers with high levels of education and skills. According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor David Autor, demand for skills has consistently increased across developed countries. The skill premium, then, is a result of skills not being supplied at a rate to keep up with demand. The proposed solution to inequality driven by these trends is increasing education and job training opportunities for workers so they can get better paying jobs. A second explanation is trade and globalization. Scholars, including Autor, point to increases in trade and offshoring as a cause of income inequality. According to this hypothesis, growing trade between the United States and the rest of the world, especially China, has increased the number of imports in the U.S. economy, which has led to job loss in industries that originally produced these goods in the United States. Offshoring has also affected jobs and wages. Both these trade phenomena lead to declining employment, falling labor force participation, and weak inflation-adjusted wage growth. Possible policy solutions for this trend include those that would make U.S. exports more competitive, among them the depreciation of the U.S. dollar. The last explanation suggests that U.S. government policies created an institutional framework that led to increasing inequality. Since the late 1970s, deregulation, de-unionization, tax changes, federal monetary policies, “the shareholder revolution,” and other policies reduced wages and employment. This explanation would seem to call for policy changes such as increasing unionization, better supervision of Wall Street, raising the minimum wage, and maintaining a full-employment focus in monetary policy, to address inequality and declining wages. These three main explanations for income inequality show the difficulty in pointing to one cause of inequality over others. Researchers’ emphasis on disentangling causes of income inequality is relevant to understanding the issue, but it also highlights the complexity of factors that contribute to labor market inequality. Income inequality has no one cause. As such, any policy solutions that address inequality must match this nuance and acknowledge the various factors that contribute to inequality. Tangles of pathology Trilemmas are always fun. Let’s do one. You may pick two, but no more than two, of the following:

By “inequality”, I mean high dispersion of economic outcomes between individuals over full lifetimes. [1] By “nonpathology”, I mean the absence of a sizable underclass within which institutions of social cohesion — families (nuclear and extended), civic and religious organizations — function poorly or at best patchily, in which conflict and violence are frequent and economic outcomes are poor. From the inside, a pathologized underclass perceives itself as simultaneously dysfunctional and victimized. From the outside, it is viewed culturally and/or morally deficient, and perhaps inferior genetically. Whatever its causes and whomever is to blame, pathology itself is a real phenomenon, not just a matter of false perception by dominant groups. This trilemma is not a logical necessity. It is possible to imagine a liberal society that is very unequal, in which rich and poor alike make the best of their circumstances without clumping into culturally distinct groupings, in which shared procedural norms render the society politically stable despite profound quality of life differences between winners and losers. But I think empirically, no such thing has existed in the world, and that no such thing ever will given how humans actually behave. It’s easy to find examples of societies with any two of liberalism, inequality, and nonpathology. You can have inequality in feudal or caste-based societies without pathology. The high castes may well perceive the low castes as inferior, and the low castes may regret their circumstances. But with the hierarchy sustained by overt force and a dominant ideology of staying in place, there is no need for pathology. Families and religious organizations in the lower castes might be strong, there may be little internal conflict, and no perception inside or outside the low status group that they are violating the norms of their society. There are simply overt and customary relations of domination and subordination. This was the situation of slaves in the American South prior to emancipation. They faced an unhappy and unjust circumstance, but a straightforward one. Whatever instabilities of family life or institutional deficiencies slaves endured were overtly forced upon them, and cannot reasonably be attributed to pathologies of the community, particularly given the experience of early Reconstruction. (More on this below.) Contemporary Nordic countries do a fair job of combining liberalism and nonpathology. But that is only possible because they constitute unusually equal societies. The United States today, of course, chooses liberalism and inequality, and so, I claim, it cannot survive without pathology. Why not? In a liberal society, humans segregate into groups based on economic circumstance. Economic losers become geographically and socially concentrated, and are not persuaded by the gloats of economic winners that outcomes were procedurally fair and should be quietly accepted. Unequal outcomes are persistent. As an empirical matter we know there is never very much rank-order economic mobility in unequal societies (nor should we expect or even wish that there would be). That should not be surprising, because the habits and skills and connections and resources that predict economic success will be disproportionately available within the self-segregated communities of winners. So, even if we stipulate for some hypothetical first generation that outcomes were procedurally fair, outcomes for future generations will be very strongly biased towards class continuity. Equality of opportunity cannot coexist with inequality of outcome unless the political community forcibly and illiberally integrates winners and losers (and perhaps not even then). But an absence of equality of opportunity is incompatible with the political basis of liberal society. If numerous losers are enfranchised and well-organized, they will seek and achieve redress (redistribution of social and economic goods and/or forced integration), or else the society must drop its pretense of liberalism and disenfranchise the losers, or at least concede the emptiness of any claim to legitimacy based on equality of opportunity. Pathology permits a circumvention of this dilemma. It enables a reconciliation of equal opportunity with persistently skewed outcomes by claiming that persistent losers simply fail to seize the opportunities before them, as a result of their individual and communal deficiencies. Conflict within and between communities and the chaos of everyday life reduce the likelihood that even a very numerous pathologized underclass will effectively dispute the question politically. Conflict and “broken institutions” also serve as ipso facto explanations for sub-par outcomes. If the losers are sufficiently pathologized, it is possible to reconcile a liberal society with severe inequality. If they are not, the contradictions become difficult to paper over. This may seem a very functional and teleological, some might even say conspiratorial, account of social pathology. It’s one thing to argue that it would be convenient, from an amoral social stability perspective, for the losers in an unequal society to behave in ways that appear from the perspective of winners to be pathological and that prevent losers from organizing to press a case the might upset the status quo. It’s another thing entirely to assert that so convenient a pathology would actually arise. After all, humans flourish when they belong to stable families, when they participate in civic and professional organizations, and when their communities are not riven by conflict and violence. Why would the combination of liberalism, inequality, and pathology be stable, when the underclass community could simply opt out of behaving pathologically? Individual communities can opt out. Some do. But unless those communities embrace norms that eschew conventional socioeconomic pecking orders and/or political engagement with the larger polity (e.g. the Amish), it is entirely unstable for those nonpathological communities to remain underclass in a liberal polity. Suppose there were a community constituted of stable, traditional families. Its members were diligent, forward-looking, and hardworking, pursued education and responded to labor market incentives. And suppose this community was politically engaged, pressing its perspective and interests in government at all levels. In a liberal polity, it is just not supportable for such a community to remain a socioeconomic underclass. One of two things may happen: the community may press its case with the liberal establishment, identify barriers to the success of its members and work politically to overcome them, and eventually integrate into the affluent “middle class”. But if all underclass communities were to succeed in this way, there could be no underclass at all, there would be a massive decrease in inequality. Nonpathology requires equality. Alternatively, if severe inequality is going to continue, then there must remain some sizable contingent of people who are socioeconomic losers, who will as a matter of economic necessity become segregated into less-desirable neighborhoods, who will come to form new communities with social identities, which must be pathological for their poverty to be stable. Particular communities can opt out of pathology, but it is a fallacy of composition to suggest that that all communities can opt out of pathology in a polity that will remain both liberal and unequal. If a society is, at a certain moment in time, deeply unequal, then pathology among the poor is required if status quo winners are to preserve their place, which, under sufficient dispersion of circumstance, can become a nearly existential concern for them. Consider the perspective of a liberal and well-intentioned member of the wealthy ruling elite of a poor, developing country. To “live as ordinary citizens live” would entail renouncing civilized life as she understands it. It would entail becoming a kind of barbarian. I don’t think the perspective of elites in less extreme but still unequal developed countries is all that different. Liberal elites need not and do not set about intentionally manufacturing pathology. They simply manage the arrangement of political and social institutions with a shared, tacit, and perfectly natural understanding that their own reduction to barbarism would count as a bad policy outcome and should be avoided. The set of policy arrangements consistent with this red line just happens to be disjoint from the set of arrangements under which there would not exist pathologized communities. Elite non-barabarism depends upon inequality, upon a highly skewed distribution of consumption and of the insurance embedded in financial claims, which must have justification. Elite non-barbarism may also depend very directly on the availability of cheap, low-skill labor. Liberal elites may be perfectly sincere in their handwringing at the state of the pathologized poor, laudable in their desire to “discover solutions”. Consider The Brookings Institution. But, under the constraints elites tacitly place on the solution space, the problems really are insoluble. The best a liberal policy apparatus can do is to resort to a kind of clientism in which the pathology of the underclass is handwrung and bemoaned, but nevertheless acknowledged as the cause and justification for continued disparity. Instruction (however futile) and a stigmatized means-tested “safety net” are sufficient to signal elites’ good intentions to themselves and absolve them of any need to revise their self-perceptions as civilized and liberal. If pathology is necessary, it is also easy to get. Self-serving (mis)perceptions of pathology by elites of a poor community become self-fulfilling. Elites fearful of a “pathological” community will be more cautious about collaborating with their members economically, or hiring them. Privately, employers will subject members of the allegedly pathological community to more monitoring, impose more severe punishments based on less stringent evidence than they would upon members of communities that they trust. Publicly, concern over a community’s perceived pathology will translate to more intensive policing and laws or norms that de facto give authorities a freer hand among communities perceived to be pathological. Holding behavior constant, police attention creates crime, and a prevalence of high crime is ipso facto evidence of pathology. Of course, as pathology develops, behavior may not remain constant. Intensive monitoring (public and private) and the “positives” resulting from extra scrutiny justify ever more invasive monitoring and interference by authorities, which leads the monitored communities to very reasonably distrust formal authority. Cautiousness among employers contributes to economic precarity within the monitored community. Communities that distrust formal authority are like tiny failed statelets. Informal protection rackets arise to fill roles that formal authority no longer can. If no hegemon arises then these protection rackets become competitive and violent — “gangs!” — which constitute yet more clear evidence of pathology to outsiders. Economic precarity and employment disadvantage render informal and illicit economic activity disproportionately attractive, leading mechanically to more crime and sometimes quite directly to pathology, because some activities are illicit for a reason (e.g. heroin use). The mix of economic precarity and urban density loosens male attachment to families, a fact which has been observed not only recently and here but over centuries and everywhere, which increases poverty among women and children and engenders cross-generational pathology. Poverty itself becomes pathology within communities unable to pool risk beyond direct, also-poor acquaintances. Behavior that is perfectly rational for the atomized poor — acquiescence to unpleasant tradeoffs under conditions of crisis — appear pathological to affluent people who “would never make those choices” because they would never face those circumstances. About a year ago, there was a rather extraordinary conversation between Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jonathan Chait. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] At a certain point, Chait argues that the experience of white supremacy and brutality would naturally have left “a cultural residue” that might explain what some contemporary observers view as pathology. Coates responds: What about the idea that white supremacy necessarily “bred a cultural residue that itself became an impediment to success”? Chait believes that it’s “bizarre” to think otherwise. I think it’s bizarre that he doesn’t bother to see if his argument is actually true. Oppression might well produce a culture of failure. It might also produce a warrior spirit and a deep commitment to attaining the very things which had been so often withheld from you. There is no need for theorizing. The answers are knowable. There certainly is no era more oppressive for black people than their 250 years of enslavement in this country. Slavery encompassed not just forced labor, but a ban on black literacy, the vending of black children, the regular rape of black women, and the lack of legal standing for black marriage. Like Chait, 19th-century Northern white reformers coming South after the Civil War expected to find “a cultural residue that itself became an impediment to success.” In his masterful history, Reconstruction, the historian Eric Foner recounts the experience of the progressives who came to the South as teachers in black schools. The reformers “had little previous contact with blacks” and their views were largely cribbed from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They thus believed blacks to be culturally degraded and lacking in family instincts, prone to lie and steal, and generally opposed to self-reliance: Few Northerners involved in black education could rise above the conviction that slavery had produced a “degraded” people, in dire need of instruction in frugality, temperance, honesty, and the dignity of labor … In classrooms, alphabet drills and multiplication tables alternated with exhortations to piety, cleanliness, and punctuality. In short, white progressives coming South expected to find a black community suffering the effects of not just oppression but its “cultural residue.” Here is what they actually found: During the Civil War, John Eaton, who, like many whites, believed that slavery had destroyed the sense of family obligation, was astonished by the eagerness with which former slaves in contraband camps legalized their marriage bonds. The same pattern was repeated when the Freedmen’s Bureau and state governments made it possible to register and solemnize slave unions. Many families, in addition, adopted the children of deceased relatives and friends, rather than see them apprenticed to white masters or placed in Freedmen’s Bureau orphanages. By 1870, a large majority of blacks lived in two-parent family households, a fact that can be gleaned from the manuscript census returns but also “quite incidentally” from the Congressional Ku Klux Klan hearings, which recorded countless instances of victims assaulted in their homes, “the husband and wife in bed, and … their little children beside them.” This, I think, is a biting takedown of one theory of social pathology, that it arises as a sort of community-psychological reaction to trauma, an explanation that is simultaneously exculpatory and infantilizing. The “tangle of pathology” that Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously attributed to the black community did not refer to people newly freed from brutal chattel slavery in the late 1860s. It did not refer even to people in the near-contemporary Jim Crow South, people overtly subjugated by state power and threatened with cross-burnings and lynchings. No, the Moynihan report referred specifically to “urban ghettos”, mostly in the liberal North. The black community endured, in poverty and oppression but largely without “pathology”, precisely where it remained oppressed most overtly. For a brief period during Reconstruction, the contradictions between imported liberalism, non-negotiable inequality, and a not-all-at-pathological community of freedman flared uncomfortably bright. But before long (after, Coates points out, literal coupsagainst the new liberal order), the South reverted to the balance it had always chosen, sacrificing liberalism for overt domination which permitted both inequality and a black community that lived “decently” according to prevailing norms but was kept unapologetically in its place. Social pathology may be pathological for specific affected communities, but it is adaptive for the societies in which it arises. Like markets, pathology constitutes a functional solution to the problem of reconciling the necessity of social control with liberalism, which disavows many overt forms of coercion. A liberal society is a market society, because if identifiable authorities aren’t going to tell people what to do and force them, if necessary, to act, then a faceless, quasinatural market must do so. A liberal, unequal society “suffers from social pathology”, because the communities into which its losers collect must be pathological to remain so unequal. No claims are made here about causality. It is possible that some communities of people are, genetically or by virtue of some preexisting circumstance, prone to pathology, and pathology engenders inequality. It is possible that dispersion of economic outcomes is in some sense “prior”, and then absence of pathology becomes inconsistent with important social stability goals. Our trilemma is an equilibrium constraint, not a narrative. Whichever way you like to tell the story, a liberal society whose social arrangements would be badly upset by egalitarian outcomes must have pathology to sustain its underclass. The less consistent the requirements of civilized life among elites are with egalitarian outcomes, the greater the scale of pathology required to support the dispersion. That, fundamentally, is what all the handwringing in books like Coming Apart andOur Kids is about. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed