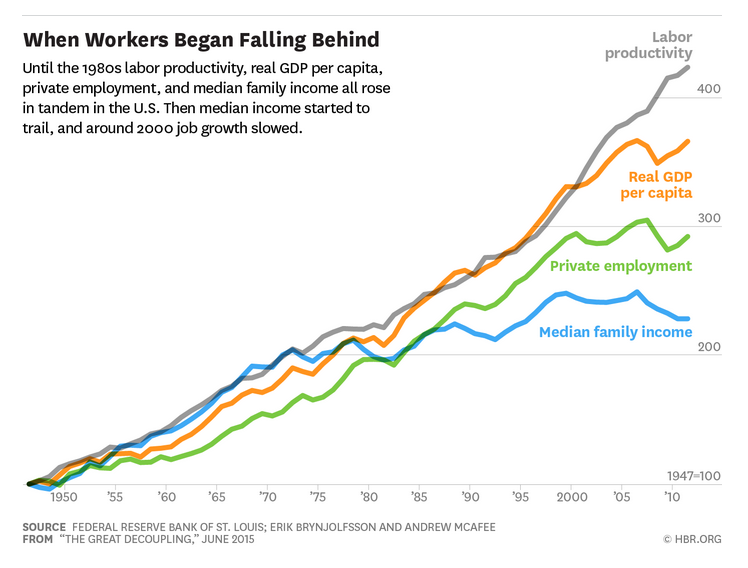

Brynjolfsson: Let’s look at the four key measures of an economy’s health: per capita GDP, labor productivity, the number of jobs, and median household income. When we studied the U.S. data on all those metrics, we turned up an intriguing story: For more than three decades after World War II, all four went up steadily and in almost perfect lockstep. Job growth and wage growth, in other words, kept pace with gains in output and productivity. American workers not only created more wealth but also captured a proportional share of the gains.

In the 1980s, however, the growth in median income began to sputter. In the past 15 years it’s turned negative; once you adjust for inflation, an American household at the 50th percentile of income distribution earns less today than it did in 1998, even after accounting for changes in household size. Job growth in the private sector has also slowed—and not just because of the 2008 recession. Job gains were anemic throughout the 2000s, even when the economy was expanding. This phenomenon is what we call the Great Decoupling. The two halves of the cycle of prosperity are no longer married: Economic abundance, as exemplified by GDP and productivity, has remained on an upward trajectory, but the income and job prospects for typical workers have faltered.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed