"The most ironic thing about rising inequality is how completely unnecessary and self-defeating it is. If we do something about it, if we adjust our policies in the way that, say, Franklin D. Roosevelt did during the Great Depression—so that we help the 99 percent and preempt the revolutionaries and crazies, the ones with the pitchforks—that will be the best thing possible for us rich folks, too. It’s not just that we’ll escape with our lives; it’s that we’ll most certainly get even richer."

|

Via Politico.

"The most ironic thing about rising inequality is how completely unnecessary and self-defeating it is. If we do something about it, if we adjust our policies in the way that, say, Franklin D. Roosevelt did during the Great Depression—so that we help the 99 percent and preempt the revolutionaries and crazies, the ones with the pitchforks—that will be the best thing possible for us rich folks, too. It’s not just that we’ll escape with our lives; it’s that we’ll most certainly get even richer."

0 Comments

Steve Waldman once again articulates issues I struggle with in Economics. I believe we create false dichotomies between positive and normative analysis, between equity and efficiency, and I believe we argue for trade liberalization without any intention of requiring those who benefit to compensate those who lose. We do this to our great shame and to the detriment of our societies that we are supposed to serve.

Waldman: "When economics tried to put itself on a scientific basis by recasting utility in strictly ordinal terms, it threatened to perfect itself to uselessness. Summations of utility or surplus were rendered incoherent. The discipline’s new pretension to science did not lead to reconsideration of its (unscientific) conflation of voluntary choice with welfare improvement. So it remained possible for economists to recommend policies that would allow some people to be made better off (in the sense that they would choose their new circumstance over the old), so long as no one was made worse off (no one would actively prefer the status quo ante). “Pareto improvements” remained defensible as welfare-improving. But, very little of what economists had previously understood to be good policy could be justified under so strict a criterion. Even the crown jewel of classical liberal economics, the Ricardian case for free trade, cannot meet the test. As John Hicks memorably put it, the caution implied by the new “economic positivism might easily become an excuse for the shirking of live issues, very conducive to the euthanasia of our science.” As one economist put it: The only concrete form that has been proposed for [a social welfare function grounded in ordinal utilities] is the compensation principal developed by Hotelling. Suppose the current situation is to be compared with another possible situation. Each individual is asked how much he is willing to pay to change to the new situation; negative amounts mean that the individual demands compensation for the change. The possible situation is said to be better than the current one if the algebraic sum of all the amounts offered is positive. Unfortunately, as pointed out by T. de Scitovsky, it may well happen that situation B may be preferred to situation A when A is the current situation, while A may be preferred to B when B is the current situation. Thus, the compensation principal does not provide a true ordering of social decisions. It is the purpose of this note to show that this phenomenon is very general. That economist was Kenneth Arrow. “This note“, circulated at The Rand Corporation, was the first draft of what later become known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. It is not, actually, an obscure result, this impossibility of separating “efficiency” from distribution. The only place you will not find it is in most introductory economics textbooks, which describe an “equity” / “efficiency” trade-off without pointing out that the size of the proverbial pie in fact depends upon how you slice it." The welfare theorems are often taken as the justification for claims that distributional questions and market efficiency can be treated as “separate” concerns. After all, we can choose any distribution, and the market will do the right thing. Yes, but the welfare theorems also imply we must establish the desired distribution prior to permitting exchange, or else markets will do precisely the wrong thing, irreversibly and irredeemably. Choosing a distribution is prerequisite to good outcomes. Distribution and market efficiency are about as “separable” as mailing a letter is from writing an address. Sure, you can drop a letter in the mail without writing an address, or you can write an address on a letter you keep in a drawer, but in neither case will the letter find its recipient. The address must be written on the letter before the envelope is mailed. The fact that any address you like may be written on the letter wouldn’t normally provoke us to describe these two activities as “separable”. In it I talked about how national, not global inequality, is the appropriate dimension for measuring inequality and I how believe it is an urgent priority for developed countries to address income inequality so as to promote economic growth. While I think the article Is quite good, I failed to draw a proper distinction between rich countries and poor countries, and, perhaps by extension, inadvertently suggested that they faced the same trade-offs. This issue was identified by Brent, who has added much to this blog. Unfortunately the article went to press before I could incorporate Brent's comments - a result which was entirely due to my procrastination of the deadline. Brent more than any other friendship has helped me through the years refine my thinking, our relationship is something I dearly cherish.

Brent suggested the following: Perhaps more to your purposes as an addendum, a direct quote from Wilkinson: "Although economic growth remains important in poorer countries, across the richest 25 or 30 countries, there is no tendency whatsoever for health to be better among the most affluent rather than the least affluent of these rich countries. The same is also true of levels of violence, teenage pregnancy rates, literacy and maths scores among school children, and even obesity rates. In poorer countries both inequality and economic growth are important to outcomes such as health, but rich countries have reaches a level of development beyond which further rises in material living standards do not help reduce health or social problems. While greater equality is important at all levels of economic development, the connection between life expectancy and Gross National Income per head weakens as countries get richer until, among the very riches countries, the connection disappears entirely." Brent also sent me this link and this note on the topic. Primarily I thought the Dolen link could be useful as an addendum because of your article's discussion of cross-country comparison respective of GDP per capita. The Dolen link: o gave SPI vs. GDP per capita (at PPP) for a much wider basket of countries than the basket of countries shown in the figure 7 that you provided in your article (and so might be useful because your article didn't state a restriction to developed countries); and o gave the line "we could say that for the poorer countries, GDP “explains” about two-thirds of differences in SPIs, but for the wealthier countries, only about one third." (and so might be useful because of your intended focus on developed countries, and further useful as a direct quote as opposed to your interpretation of a video). Commit suicide......Via Zerohedge. The Copper rehypothecation issue is something I have been covering for two years.

Can we say monetization boys and girls? -sure I knew you could. Its a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

NY Times (Thanks Brent)

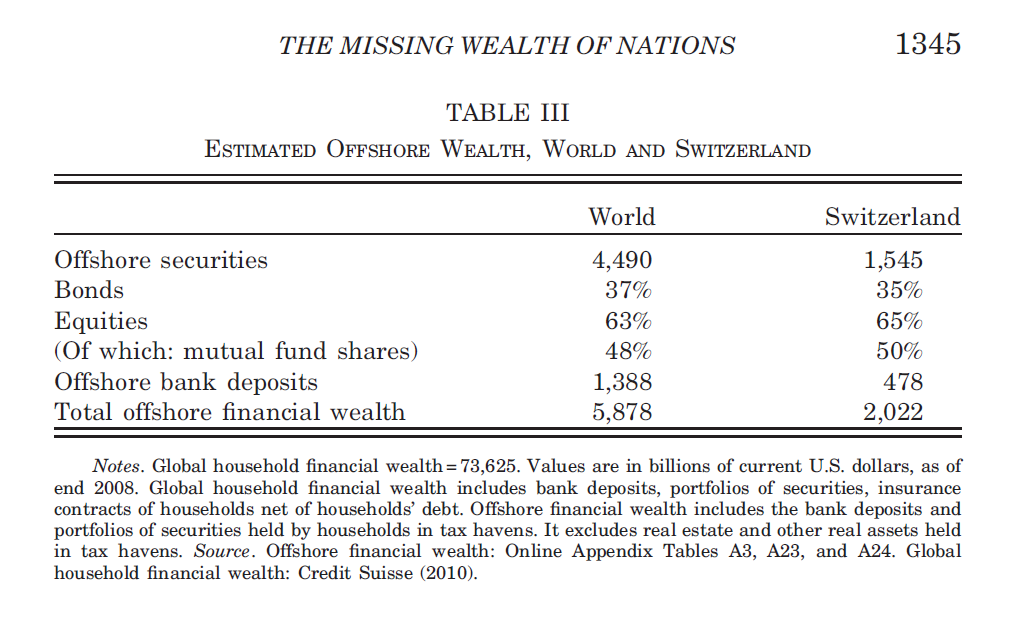

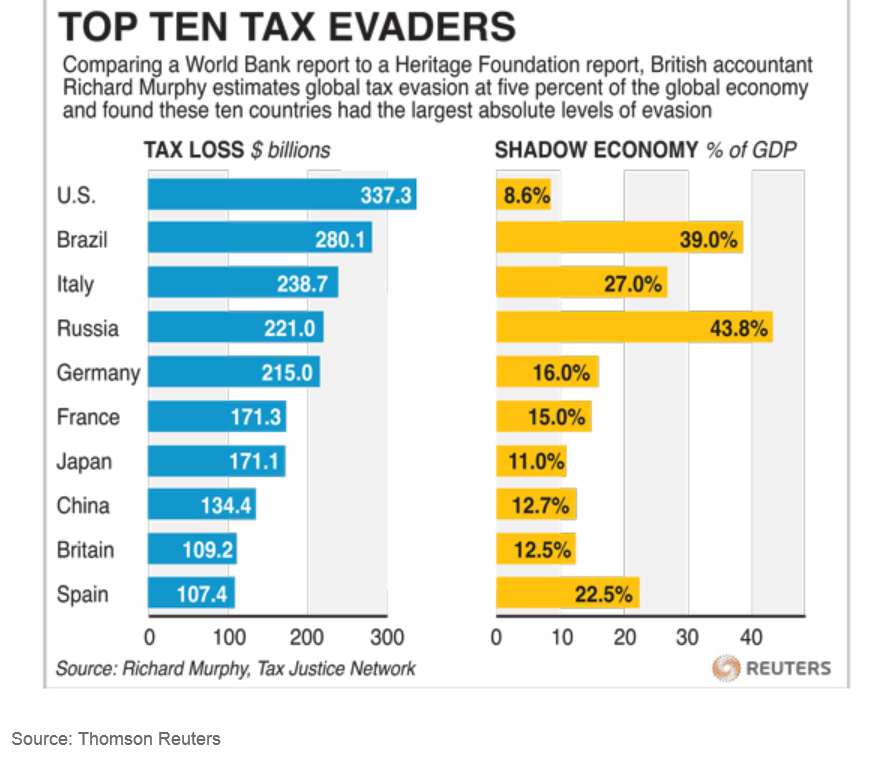

Krugman quotes economist Gabriel Zucman’s (2013) research ‘The Missing Wealth of Nations: Are Europe and the US Net Debtors or Net Creditors?’ attempts to empirically quantify the wealth hidden in tax havens. Abstract: This article shows that official statistics substantially underestimate the net foreign asset positions of rich countries because they fail to capture most of the assets held by households in offshore tax havens. Drawing on a unique Swiss data set and exploiting systematic anomalies in countries’ portfolio investment positions, I find that around 8% of the global financial wealth of households is held in tax havens, three-quarters of which goes unrecorded. On the basis of plausible assumptions, accounting for unrecorded assets turns the eurozone, officially the world’s second largest net debtor, into a net creditor. It also reduces the U.S. net debt significantly. The results shed new light on global imbalances and challenge the widespread view that after a decade of poor-to-rich capital flows, external assets are now in poor countries and debts in rich countries. I provide concrete proposals to improve international statistics. In contrast, in the documentary Tax Free Tour, James S Henry, the former chief economist of the McKinsey & Co estimates that in 2010, 21-32 trillion dollars of the world’s wealth is hidden in offshore tax havens with two thirds of the offshore money coming from the developed world. But the elites are not content to merely politically engineer historically low tax levels for themselves. Many of them move their wealth into tax havens where they blur the lines between tax avoidance and tax evasion. Banks, eager to serve and retain their elite clients, are enabling and facilitating these corrupt practices. From Zerohedge: "Credit Suisse made false claims in US visa applications, conducted business with clients in secret elevators and shredded documents to help more than 22,000 American customers avoid US taxes, according to a scathing report by a US congressional committee.” Sounds about right by proportions. Via Motherboard

|

Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed