|

Excellent interviews from Bass, Hussman, Rosenberg, and PIMCO. A veritable cornucopia of my favorite bears.

0 Comments

BIS summarizes what I have repeatedly been saying about CBs creating systemic risk. Quoted in Hussman's latest weekly commentary.

“Originally forged as a description of central bank actions to prevent financial collapse, the phrase ‘whatever it takes’ has become a rallying cry for central banks to continue their extraordinary actions. But we are past the height of the crisis, and the goal of policy has changed – to return still-sluggish economies to strong and sustainable growth. Can central banks now really do ‘whatever it takes’ to achieve that goal? As each day goes by, it seems less and less likely. Central banks cannot repair the balance sheets of households and financial institutions. Central banks cannot ensure the sustainability of fiscal finances. And, most of all, central banks cannot enact the structural economic and financial reforms needed to return economies to the real growth paths authorities and their publics both want and expect. “What central bank accommodation has done during the recovery is to borrow time – time for balance sheet repair, time for fiscal consolidation, and time for reforms to restore productivity growth. But the time has not been well used, as continued low interest rates and unconventional policies have made it easy for the private sector to postpone deleveraging, easy for the government to finance deficits, and easy for the authorities to delay needed reforms in the real economy and in the financial system. After all, cheap money makes it easier to borrow than to save, easier to spend than to tax, easier to remain the same than to change. “Alas, central banks cannot do more without compounding the risks they have already created. Instead, they must re-emphasise their traditional focus – albeit expanded to include financial stability – and thereby encourage needed adjustments rather than retard them with near-zero interest rates and purchases of ever larger quantities of government securities. And they must urge authorities to speed up reforms in labour and product markets, reforms that will enhance productivity and encourage employment growth rather than provide the false comfort that it will be easier later.” I have been saying this for years. One of my challenges is that I see things many years in advance. As a friend of mine once told me, there is no corporate market for that skill. Isn't it rich? Isn't it queer? Losing my timing this late in my career. And where are the clowns? There ought to be clowns... Well, maybe next year. via Hussman.

Interestingly, the minutes of the Federal Reserve’s May 17 meeting indicated a significant shift away from the idea that QE is supporting the economy, toward concerns that it is creating distortions: “There is also concern about the possibility of a breakout of inflation, although current inflation risk is not considered manageable, and of an unsustainable bubble in equity and fixed-income markets given current prices… Net interest margins are very compressed, making favorable earnings trends difficult and encouraging banks to take on more risk. The Fed’s aggressive purchases of 15-year and 30-year MBS have depressed yields for the ‘bread and butter’ investment in most bank portfolios; banks seeking additional yield have had to turn to investment options with longer durations, lower liquidity, and/or higher credit risk… Uncertainty exists about how markets will reestablish normal valuations when the Fed withdraws from the market. It will likely be difficult to unwind policy accommodation, and the end of monetary easing may be painful for consumers and businesses.” Very timely given the sell off in gold and other commodities today (China disappointed- SURPRISE! :)).

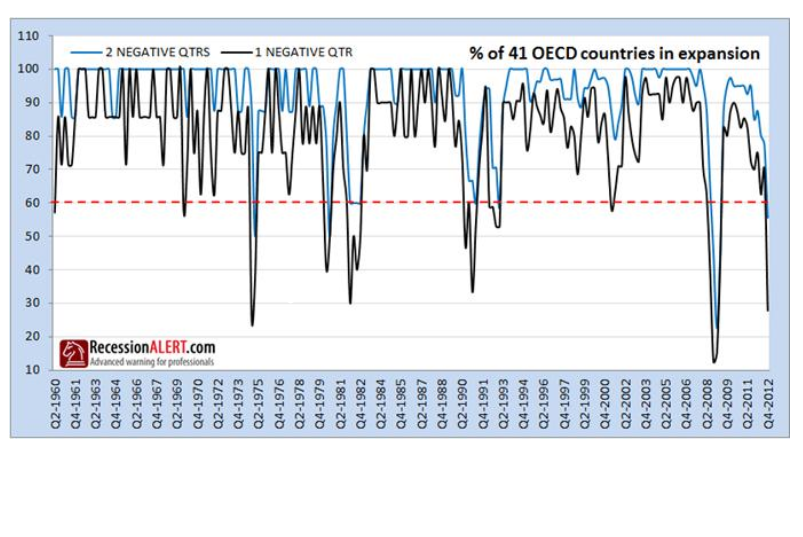

Here is an excerpt: "With respect to QE, the evidence indicates that quantitative easing is not rocket fuel – at best, it is a bungee cord; reasonably effective in helping confidence and risk premiums normalize when they have spiked in response to fear over the prior 6-months, and capable of releasing just enough pent-up demand to kick a can, but with little durable economic effect once short-term interest rates have hit the zero bound (which was nearly $2 trillion ago). We’re really left with are arguments that hinge on superstition – effectively arguments that “the Fed can do this forever, and it’s not going to stop.” There's no problem with claiming that QE outweighs all other considerations, in the same way that we've found that extreme overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions often outweigh trend-following onsiderations. Just make sure that this faith in QE is justified. I don't believe it is. My impression is that this is the claim; that quantitative easing, in and of itself, is a lucky rabbit’s foot, and that it changes everything, by mechanisms that investors need not understand, and makes all historical evidence and analysis irrelevant; that despite the historically tight and economically tractable relationship between corporate surpluses and the combined deficits of government and households**, somehow this time is different, and profit margins will remain elevated forever. I doubt that any of this will prove to be correct, but as John Kenneth Galbraith wrote in 1954 about the Great Crash, “the time had come, as in all periods of speculation, when men sought not to be persuaded by the reality of things but to find excuses for escaping into the new world of fantasy.” That what I said. "I see the incessant focus on the power of the central bank to manage an economy as being misguided and inappropriate. The world reached a financial crisis principally because of a lack of proper regulation and enforcement of the financial services industry. In addtion to this, the Eurozone reached their crisis because they gave up their currencies, and the global trade system shifted production to Germany for high valued manufacturing and China for low valued manufacturing. Regardless of the price level, these economies are not going to generate jobs for their unemployed. Many academics and market participants who view religion as nothing more than superstition, seem to have elevated the central banks to Christ-like status. If we want to eat bread and wine, we need to start growing some wheat and grapes and stop asking the central bank to 'make do' with the water and loaf we left in the toilet." "I’ve been fascinated in recent weeks by the rather intense gap between the unrestrained economic optimism of Wall Street and the actual data." Here is a picture that sums up the reality of OECD economic performance.

Let's just say he better not volunteer to man the phone lines at the suicide/crisis hotline.

I am also a fan of Zig Ziglar. US entered a recession in Q3.

"At present, we have little reason to believe that the data-generating process we are observing here is anything “out-of-sample” from the standpoint of a century of historical evidence."

I disagree, the level of global indebtednss is unprecedented, as is the concommitant level of central bank intervention. From his Annual Report.

"Economies can retreat from excessive debt burdens in three ways. One is “austerity,” where spending is restricted in the attempt to reduce deficits and keep debt burdens from growing as fast as the economy grows. The difficulty with austerity is that it is often self-defeating because economic growth slows and tax revenues often decline enough to offset the reduced spending. A second approach is “monetization,” where the central bank creates currency and bank reserves in order to purchase and effectively retire government debt. This approach may be expedient in the short-term, but can lead to severe inflationary effects in the longer-term. A final approach is “debt restructuring,” where bad debts are written down or swapped for a direct ownership claim on some other asset (known as “debt-equity swaps”). This approach can detach the economy from the burden of prior debts, but it is most contentious politically because it requires lenders to take losses or accept changes in the structure of their claims. In the next several years, it seems inescapable that the U.S and Europe will require a combination of all three approaches. In my view, the likelihood of addressing global debt problems without significant economic and political turbulence is quite low. The primary question is whether losses and debt restructuring will be imposed on lenders who voluntarily accepted the risks, or whether the losses will instead be inflicted on the public through austerity and inflation. My impression is that the answer will be a combination of all of these, and that the ability to navigate a broad range of potential outcomes will be required. Meanwhile, I remain skeptical that central bank interventions targeted at making investors feel “wealthier” will have much real economic effect, or will durably reduce the need for difficult economic adjustments." I think this is the "uncertainty" that is holding back business investment more than anything. The central banks are railing against deflation and the market doesn't know whether they will suceed or fail. ( I vote fail.) "So what do I worry about? I worry that investors forget how devastating a deep investment loss can be on a portfolio. I worry that the constant hope for central bank action has given investors a false sense of security that recessions and deep market downturns can be made obsolete. I worry that the depth of the recessions and downturns – when they occur – will be much deeper precisely because of the speculation, moral hazard, and misallocation of resources that monetary authorities have encouraged. I worry that both a global recession and severe market downturn are closer at hand than investors assume, partly despite, and partly because, they have so fully embraced the illusory salvation of monetary intervention."

This is a theme I have discusssed on these pages. Specifically here, seven months ago, where I said: "I see the incessant focus on the power of the central bank to manage an economy as being misguided and inappropriate. The world reached a financial crisis principally because of a lack of proper regulation and enforcement of the financial services industry. In addtion to this, the Eurozone reached their crisis because they gave up their currencies, and the global trade system shifted production to Germany for high valued manufacturing and China for low valued manufacturing. Regardless of the price level, these economies are not going to generate jobs for their unemployed. Many academics and market participants who view religion as nothing more than superstition, seem to have elevated the central banks to Christ-like status. " |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed