|

Can Economics Change Your Mind?

Economics is sometimes dismissed as more art than science. In this skeptical view, economists and those who read economics are locked into ideologically motivated beliefs—liberals versus conservatives, for example—and just pick whatever empirical evidence supports those pre-conceived positions. I say this is wrong and solid empirical evidence, even of the complicated econometric sort, changes plenty of minds. For one thing, it's changed my mind. Work from David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson has convinced me that in some local areas the job losses from free trade can be substantial, and that these communities have been slower to adjust than I expected. Importantly, the study is not simple and utilizes instrumental variables, representing the kind of econometrics that skeptics think can't convince anyone. Another example is, Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody's Analytics, who tells me the paper "Potential Output and Recessions: Are We Fooling Ourselves?" by Robert Martin, Teyanna Munyan, and Beth Anne Wilson changed his mind recently. This study suggests that recessions tend to have a permanent negative effect on output, which was previously not thought to be the case. As a result Moody's Analytics is undertaking more research on this. Researchers also frequently set out to test a hypothesis they think is right, only to find it was wrong. Harvard economists Raj Chetty and John Friedman were skeptical of standardized test based measures of teacher performance, and they set off to do research, along with Jonah Rockoff, which they thought was "going to show that these measures don’t work, that this has to do with student motivation or principal selection or something else." Instead, their evidence convinced them they were wrong, and their results showed that value-added measures were good measures of teacher quality, and the authors argue that school districts should use them in teacher evaluations. Tyler Cowen's version here. Overall I find that history and theory-laden observation tend to be the forms of evidence which have convinced me the most. #3 and #8 are examples of “sheer econometrics,” but that is not usually how minds are changed, mine included. HBR

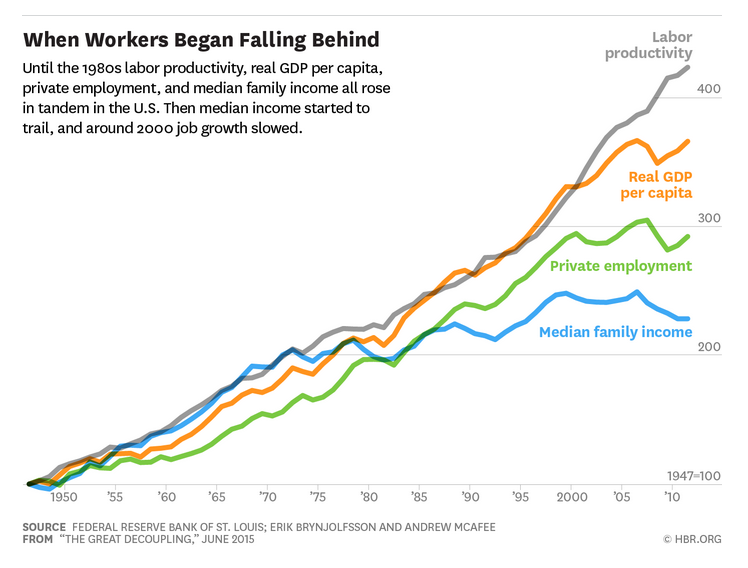

Brynjolfsson: Let’s look at the four key measures of an economy’s health: per capita GDP, labor productivity, the number of jobs, and median household income. When we studied the U.S. data on all those metrics, we turned up an intriguing story: For more than three decades after World War II, all four went up steadily and in almost perfect lockstep. Job growth and wage growth, in other words, kept pace with gains in output and productivity. American workers not only created more wealth but also captured a proportional share of the gains. In the 1980s, however, the growth in median income began to sputter. In the past 15 years it’s turned negative; once you adjust for inflation, an American household at the 50th percentile of income distribution earns less today than it did in 1998, even after accounting for changes in household size. Job growth in the private sector has also slowed—and not just because of the 2008 recession. Job gains were anemic throughout the 2000s, even when the economy was expanding. This phenomenon is what we call the Great Decoupling. The two halves of the cycle of prosperity are no longer married: Economic abundance, as exemplified by GDP and productivity, has remained on an upward trajectory, but the income and job prospects for typical workers have faltered. "What’s inexplicable is why the Obama administration pushes a trade agenda that so directly undermines the middle-class economic agenda the president says he desires to be his legacy."

Steve Waldman once again articulates issues I struggle with in Economics. I believe we create false dichotomies between positive and normative analysis, between equity and efficiency, and I believe we argue for trade liberalization without any intention of requiring those who benefit to compensate those who lose. We do this to our great shame and to the detriment of our societies that we are supposed to serve.

Waldman: "When economics tried to put itself on a scientific basis by recasting utility in strictly ordinal terms, it threatened to perfect itself to uselessness. Summations of utility or surplus were rendered incoherent. The discipline’s new pretension to science did not lead to reconsideration of its (unscientific) conflation of voluntary choice with welfare improvement. So it remained possible for economists to recommend policies that would allow some people to be made better off (in the sense that they would choose their new circumstance over the old), so long as no one was made worse off (no one would actively prefer the status quo ante). “Pareto improvements” remained defensible as welfare-improving. But, very little of what economists had previously understood to be good policy could be justified under so strict a criterion. Even the crown jewel of classical liberal economics, the Ricardian case for free trade, cannot meet the test. As John Hicks memorably put it, the caution implied by the new “economic positivism might easily become an excuse for the shirking of live issues, very conducive to the euthanasia of our science.” As one economist put it: The only concrete form that has been proposed for [a social welfare function grounded in ordinal utilities] is the compensation principal developed by Hotelling. Suppose the current situation is to be compared with another possible situation. Each individual is asked how much he is willing to pay to change to the new situation; negative amounts mean that the individual demands compensation for the change. The possible situation is said to be better than the current one if the algebraic sum of all the amounts offered is positive. Unfortunately, as pointed out by T. de Scitovsky, it may well happen that situation B may be preferred to situation A when A is the current situation, while A may be preferred to B when B is the current situation. Thus, the compensation principal does not provide a true ordering of social decisions. It is the purpose of this note to show that this phenomenon is very general. That economist was Kenneth Arrow. “This note“, circulated at The Rand Corporation, was the first draft of what later become known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. It is not, actually, an obscure result, this impossibility of separating “efficiency” from distribution. The only place you will not find it is in most introductory economics textbooks, which describe an “equity” / “efficiency” trade-off without pointing out that the size of the proverbial pie in fact depends upon how you slice it." The welfare theorems are often taken as the justification for claims that distributional questions and market efficiency can be treated as “separate” concerns. After all, we can choose any distribution, and the market will do the right thing. Yes, but the welfare theorems also imply we must establish the desired distribution prior to permitting exchange, or else markets will do precisely the wrong thing, irreversibly and irredeemably. Choosing a distribution is prerequisite to good outcomes. Distribution and market efficiency are about as “separable” as mailing a letter is from writing an address. Sure, you can drop a letter in the mail without writing an address, or you can write an address on a letter you keep in a drawer, but in neither case will the letter find its recipient. The address must be written on the letter before the envelope is mailed. The fact that any address you like may be written on the letter wouldn’t normally provoke us to describe these two activities as “separable”. Mish misses the point(again).

Pettis: Former Fed Chairman (1932-48) Marriner Eccles, who may well have been the most subtle economist of the 20th Century, from his memoir, Beckoning Frontiers (1966): As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption, mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth – not of existing wealth, but of wealth as it is currently produced – to provide men with buying power equal to the amount of goods and services offered by the nation's economic machinery. Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929-30 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of currently produced wealth. This served them as capital accumulations. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied to themselves the kind of effective demand for their products that would justify a reinvestment of their capital accumulations in new plants. In consequence, as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped. Pettis again: I will again quote Mariner Eccles, from his 1933 testimony to Congress, in which he was himself quoting with approval an unidentified economist, probably William Trufant Foster. In his testimony he said: "It is utterly impossible, as this country has demonstrated again and again, for the rich to save as much as they have been trying to save, and save anything that is worth saving. They can save idle factories and useless railroad coaches; they can save empty office buildings and closed banks; they can save paper evidences of foreign loans; but as a class they cannot save anything that is worth saving, above and beyond the amount that is made profitable by the increase of consumer buying. It is for the interests of the well-to-do, to protect them from the results of their own folly – that we should take from them a sufficient amount of their surplus to enable consumers to consume and business to operate at a profit." |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed